Renovation

by Ken Malatesta

I owned three books when I went away to college. Owning books in the blue-collar neighborhood of Chicago where I grew up was not typical and getting out from under that weight doesn’t seem as hard now as it did then. I didn’t fear being called a “pussy” which was standard for everyone no matter how many football snaps you played, but I feared seeming odd or different, or worse wanting to be. A cardinal sin of growing up in any neighborhood. I didn’t know I would major in English and I can’t help but think of its obsolescence as I stare at thirty years' worth of books stacked in my living room.

We are renovating. Purging old things.

Sometimes it feels like I am sifting through someone else’s belongings. I don’t pause to unravel the mystery of whatever significance these items once held. Handwritten letters, some from people I have trouble recalling. Even the strange intimacy of penmanship cannot overcome a memory worn by time. Receipts and business cards. Drafts of stories I have no recollection of writing. Half-finished drafts of stories I’ll never finish. Letters from former girlfriends I would be embarrassed to revisit. Five years’ worth of correspondence with a foreign exchange student from Hong Kong I met in high school and lost touch with more than 20 years ago. Bank statements dating from the late 90s, issues of Harper's magazines I saved for reasons obscured by time. All destined for the shredder. After years of attempts and periodic belabored conversations with myself, I have finally resolved to let it go. What is life if not a long exercise in learning how to let it go? (I do save a picture of that old pen pal and me, taken I don’t know when.)

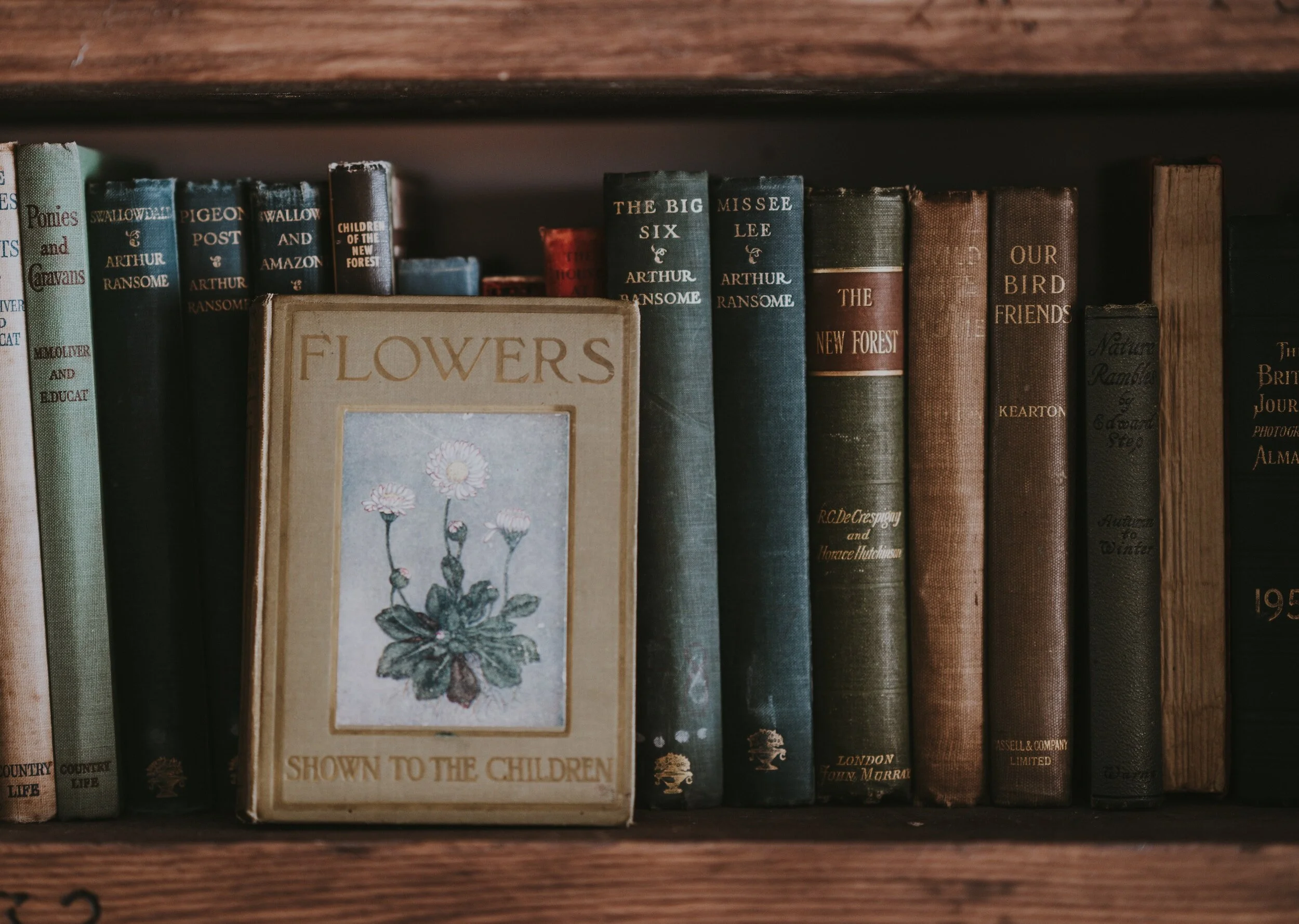

But books I can’t part with. Great conjurers, they strike with numinous force whenever I glimpse a front cover or familiar spine.

Part of the renovation entails a wall of built-in floor-to-ceiling bookshelves to hold what must be three thousand (or more, I have never counted) books my wife and I own. This is the first time in my life and our twenty years together they will be in one space. Organized (somewhat) and findable (mostly). Instead of stacked next to our bed, on dressers and end tables, on the backseats of our car, in boxes in closets, dogeared on desks and counters. The room we have renovated is an old three-season room, an addition built atop the attached garage long before we moved in. It sat unused for two years before we gradually could make it habitable. Always it held the books. 12 years of incremental renovations. Vinyl windows to replace the 60-year-old never suited for the midwestern cold jalousies. A mini-split combination heat and a/c unit. Mismatched bookshelves. 3 different couches. Paint color from white to green to gray, and now this, the coup de grace, removal of the cat-scratched, dog-stained, child-worn carpet, and the installation of the shelves.

The room is an office or library I suppose, but from the start when it was separated from the world and the rest of the house by an oak door we called it the “secret room”. Mostly because unless you lived in the house you might not know it existed. But the name imbued it with mysticism and magic that it may or may not actually possess. Our toddler sons believed.

When the floors are installed and the shelves are complete and the books are in place, I tell my wife I wouldn’t mind dying there. “That’s so sad,” she says. And maybe it is. But she understands. I am thinking of something I read twenty years ago in a Keats biography, Walker Jackson Bate’s perhaps: Keats on his deathbed wanting to be surrounded by his books. It isn’t odd what we keep with us. The few particulars we take from books. The rest is a faded essence. Keats was 25 and understood something I understand more trenchantly now. My life is on those shelves, between the pages. Next to my wife and children, I can’t imagine a greater comfort when I take my last breath.

Religions teach us not to become attached to material things or the material world. Books are material but are asomatous. Disembodied voices. Looking at the inky scrawl cover of Roberto Bolano’s The Savage Detectives resurrects my 32-year-old self. I was newly a father when a blood test revealed my liver enzymes to be so elevated I thought I’d be dead in a few months. My wife says when she looks at the tattered copy of Rimbaud's A Season in Hell and The Drunken Boat that I am forever twenty-five years old, forever wearing a decrepit pea coat, forever getting off of trains, forever drinking wine in her old apartment on Roscoe Street. I carried it folded in a pocket for years.

In the autumn of 1994 when I was seventeen and living in the Iowa Memorial Union hotel, everything I owned could fit into a duffle bag.

Over time we accumulate. Furniture, coffee mugs, photographs, papers, t-shirts, tax returns. Children. All bear the illusion of permanence. Some of us accumulate books. Not as many these days I imagine. The public library where I live in Skokie is so rife I don’t buy as many books as I used to. For me, it has always been a grave decision to invest in another’s ideas, stories, and beliefs, and place them on your wall where they become a manifestation of your ideas and beliefs.

The renovation takes more time than it should, so for weeks, our books sit in chest-high dysmorphic stacks in the front room. My wife’s friends tell her that it’s too many books. And it is, at least for our small home. It’s only recently I considered getting rid of some, and I am still reluctant. A few years ago, I sold a box of outdated education textbooks for 3 dollars. I imagine by now they are mulch. This time around I am a bit more eager to discard if only to lighten the load for my children or my wife or whoever will be tasked with them after I am gone. But it is like severing a limb. Even titles like Writer’s Market Guide 1998 and the 2006 DVD & Video Guide (a gift from my father) and the only bestseller I ever bought, The Da Vinci Code (I was curious) are cause for anxious deliberation. I considered adding Richardson’s Pamela and Dreiser’s An American Tragedy to the donation pile, but I reneged. I like the validation if only for myself. That I suffered these titles, spent hours in them. And then there is the vague feeling that I will need them again. Not necessarily to read or to reference, but to remember. The Love and Western Literature class I audited in 1999. Lit & Culture of the 20th Century junior year, War & Society my senior year. More so to remember when my sons were born. Bolano, Richard Ford, Murakami, Marías. When I fell in love with my wife—Rimbaud, Emerson, Underworld, Confederacy of Dunces, Master and Margarita, Pale Fire, A Fan’s Notes, a biography of Rilke, The Inferno for the fourth or fifth time. Pinsky’s, Durling’s, Ciardi’s translations. When my father died—Ducks, Newbury Port.

Books place me—Dharma Bums ditching Rhetoric class, late October 1994, afternoons outside of EPB in Iowa City—and I can be that self again if only for a moment. Sitting at the paint-stained table on Wolcott street re-reading Purgatorio. The Water Method Man and the rest of John Irving and Hemingway and Henry Miller during summers home from college. A Mozart biography I finished in a Super 8 in Denver en route to San Francisco and Petrarch’s Sonnets on a plane back from Italy. The Moviegoer, one of my wife’s two copies, that I read and reread three summers in a row at the Devonshire pool.

The paperback Shakespeare I read when I was still a concrete laborer. A whole shelf of Shakespeare. Dante. Sibling Guide to Birds, The Backyard Birdfeeder’s Bible, biographies of T.S. Eliot, Hart Crane, Henry II, Bob Dylan, Andy Kaufman, Cicero, Nietschze, John Reed, Dickenson, Whitman, T.E. Lawrence, Richard Burton, Byron, Keats, Gandhi, Lincoln, Edna St. Vincent Millay. The Unicorn, The Accidental Man, The Joke, The Unbearable Lightness of Being. All of Kundera. Borges. Annie Dillard. Murakami. Barbara Ehrenreich. Camus. Kafka. Woolf. Peter Orner. Didion. Franzen. Vasari. Martin Amis. Kingsley Amis. Margaret Atwood. Javier Marías. Harold Bloom. Alejandro Zambra. Walter Mosely. Francine Prose. Dashiell Hammett. Ray Carver. Aleksandar Hemon. Toni Morrison. Mary Karr. Anton Chekhov. Caroline Knapp. David Means. Baldwin. O’Connor. DeLillo. Calvino. George Saunders. Sam Lipsyte. Anne Patchett. All in neat rows.

I am forgetting names, but it doesn't matter. They’re all somewhere on the wall.

Is it strange that in private moments I count them among my friends? I come from the time when one author introduced you to another in the manner that friends do. Algorithms do this now I suppose, but I don’t pay attention.

Myths; Greek, Norse, Native American. Anthologies of poetry, essays, and stories. Italian folklore. Philosophy. Usage manuals and dictionaries. Sometimes I simply like to read the titles. Buddhism and Asian History. Religions East and West. Doubt. The Working Poor. Sites of Memory Sites of Mourning. In Praise of Nepotism. The Artificial White Man. From Dawn to Decadence. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. The Variety of Religious Experience. The Tipping Point. Montaigne’s Complete Essays. The Beginning of Wisdom. Fearful Symmetry. Ariadne’s Thread. The Invisible Man. The Twilight of American Culture. Blake’s Apocalypse. Zarathustra’s Secret. The Pound Era. Being and Nothingness. The Interpretation of Dreams. The Hero of a Thousand Faces. Gods in Every Man. A Sport and a Pastime. Lightyears. Hyperspace. Jesus’ Son. 2666. Infinite Jest. Another Country. The Man Who Became Caravaggio. Stop-Time.

Poetry, thin volumes by comparison, but in sum consume entire shelves. William Blake. Wordsworth. Billy Collins, Tony Hoagland, Elizabeth Bishop, Rita Dove, e.e. cummings, Adrienne Rich, Eugenio Montale, Dean Young, John Ashbury, Frank O’Hara.

I stopped reading poetry in middle age, but a line from Roethke’s “Far Field”, remembered suddenly one afternoon, lures me back. The Dream Songs. Marvin Bell. Plath. Neruda.

There are empty spaces for books for that I gave away or loaned, and which never returned: Catch 22, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, The Life and Death of America’s Great Cities, Yeats' Collected Poems. Underworld. And the empty spaces for books to come.

We live in an era where everything is disposable and dispensable. I feel like a stranger in it. I read somewhere that there are over a billion websites and most are dead. Untended 405 errors. Cyber detritus has no weight. It is the invisible, the empty. Everything is disposable.

Sometimes I imagine my books in boxes. It is my clearest vision of them over the past twenty years. Moving with us from place to place. I imagine my books in boxes and try not to think of myself in one under the ground composting. But I do. And isn’t that the great equalizer? The humbling of any idea or word put to a page. Still, it is beautiful to be among them.