On Spirals

Gabriela de Mendonça Gomes

James Lendall Basford, a 19th-century jeweler and watch-maker, is said to have penned that “the next best thing to the enjoyment of a good time is the recollection of it."

I spent the majority of this year, 2025, in Peru, teaching English and making my way through some of the country’s abundant historical and archeological sites. As I think about the year to come, the imagery becomes hazy, but hopeful. In this last year’s newsletter I wanted to take you, readers, on meditations of some memories of the past year, accompanied by some photographs.

Chronologically, we must start at the beginning: Lima. With sunsets and pisco sours in a beer bar in the coastal capital of Peru, my first stop in the country.

For most of the year, the landscape in Lima consists of gray vaulted skies and rain that never reaches the ground; the combination of the Humboldt Current’s cooling effects on the Pacific Ocean and the opposing Andean mountains block rain. The city remains largely under siege of clouds, and while the hours of the day slog forth, the dim lighting changes not––creating a sense of purgatorial stagnation. To this day, the city carries the affectionate title of Lima, la horrible, which originates from the title of an essay in book form by Peruvian writer Sebastián Salazar Bondy. In it, he describes the idiosyncrasies of his country’s non-representative capital. My friends who lived there their whole stays prayed for days of sun in July and, from the bluffs of Miraflores, felt like Peruvian poet Cesar Vallejo: “Today I simply suffer” in the midst of the city’s frigid humidity, its ceaseless traffic, and its cosmopolitan discontent.

Two weeks after I arrived in Peru, on my 24th birthday, I moved from the capital to Arequipa, the country’s second biggest city and my first teaching placement. Arequipa is a city encased by volcanoes, three of them: the Misti, the Chachani, and the Picchu-Picchu. The ground, always sudden and always there, was not so in Arequipa. We had earthquakes weekly––tremors, really––and the unexpected shaking of furniture legs reminded me of the nature of stability and consistency: that they are constructed. The rattling of window edges always ushered forth Marcus Aurelius’ reminder about life’s inexorable transience:

Human Life. Duration: momentary. Nature: changeable. Perception: dim. Condition of the body: decaying. Soul: spinning around. Fortune: unpredictable. Lasting fame: uncertain. Sum up: the body and its parts are a river, the soul a dream and most, life is warfare and a journey far from home, lasting reputation is oblivion.

In Peru, the mountains and volcanoes are considered to hold sacred mountain spirits, or Apus, who in Andean cosmology create and destroy, harmonize and put into place. Their stillness conjuring tremors shows us how we are carried through existence as through rushing rapids.

Next, in Nazca, the fact of my mortality came quick as I felt the hot asphalt underneath me on the tarmac of Maria Reiche Neuman Airport. The smiling copilot of my propeller plane measuredly eyeing the group five I’m in, guessing our weights. The smallest, and alone, I am sat in the back of the plane. Soon, with a nausea-dampening pill in my stomach and a thick pair of black headphones conching my ears, we are off towards the decorated desert face I am here to see: the Nazca Lines. The small plane banks fast, and my heart and stomach fall out of orientation, not merely from the abrupt maneuver, but because I also see one below me: the 935-foot geoglyph of the pelican, etched into ground over 1,500 years ago by a people themselves now dust. Between spiral-shaped subterranean aqueducts, a sand dune that grows every day and a massive necropolis bearing dug-up dreadlocked mummies, Nazca is a place where the abundance of life and the inevitability of death contrast and coexist in clarity.

The ruins of Choquequirao are sometimes known as the “sacred sister of Machu Picchu.” They span a space larger than Machu Picchu and have features like agricultural terraces whose rock wall faces are adorned with stone llamas that are unique from all other Inca ruins, but it takes 2 days of hiking to get to. I went. Although the ruins remain strong in memory, the Sisyphusian effort of stepping on my own footprints as I climb out of the same canyon I walked into mere days before presides over the entire memory. The image struck deep into the corner of my mind reserved for reminding me of harder times are the small metal cabins adorning the cliff-side’s face. They are a mere five switch-backs away, and I don’t tell myself that I can make it, I know that I can. It is a piece of knowledge I feel at my core is true, but my legs don’t concur. At this point I have hiked over 35 dusty miles in the course of three days gaining and losing 6,000 ft. of elevation over two of them. Some people on their way down into the canyon pass me and confer positive sentiments, and I appreciate it, because I know that this is what they have in store for them in some days. I wish them happy trails in return. After they pass, I find a small grassy corner and sit––and cry. The tears come before I understand that I’m crying. Exhaustion is also an emotion. I reach in my backpack and find a thin, melted bar of chocolate and, getting my fingers sweetly smeared peeling it open, bite into the soft skin, crying all the while. I look up at the houses, knowing that I will, I must make it. There is no other choice and the mid-day sun keeps beaming down. “Today, I simply suffer.” I stand up and just keep taking steps, and cry again at the top, tears sweeping my face and chest with relief. Choquequirao reminds me of the fact that we always go back the ways we came, but that the cycle is not flat.

–– that it spirals.

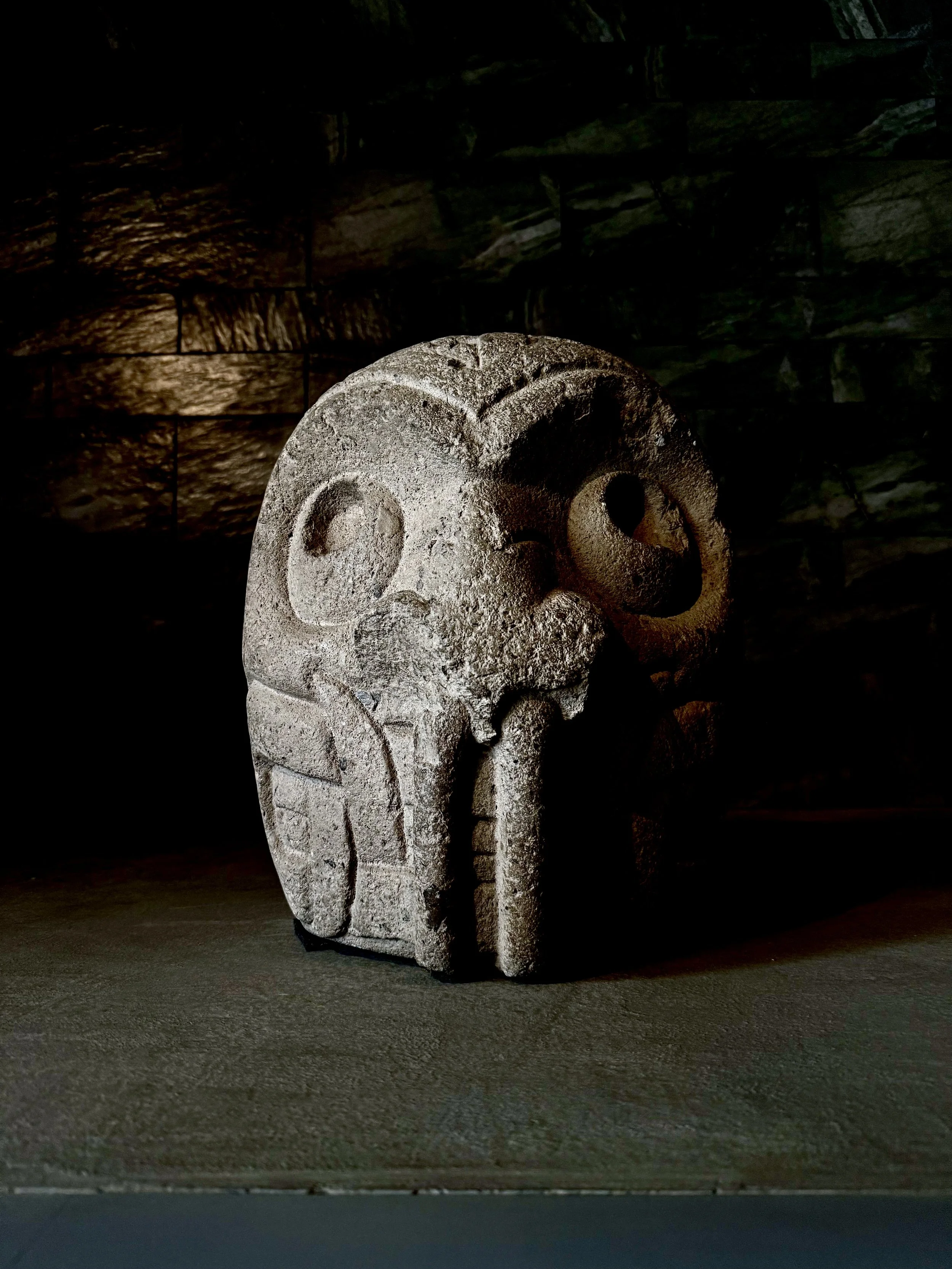

Sitting in a valley far into the small towns and tall snowed Apus of northern Peru is Chavín de Huantar, a massive archeological complex. It is a site of mixed monolithic rock, of pre-Incan construction by one of the most well-known and prolific pre-columbian peoples. Its walls are decorated with cabezas clavas depicting the physical and spiritual transition of the shaman into a sublime feline figure. I walk through the sacrificial square in the mid-day heat, beads running beneath my sunhat, imagining the ancients drinking the psychedelic San Pedro sap to commune with their gods. Walking around the buildings I find a set of stairs, steep and narrow stone steps leading underground. The stone grows colder as my feet find deeper ground. Then I reach the Old Temple’s labyrinthine galleries––long, stout tunnels. Walking through, I reach dead-end and dead-end, until one sharp turn leads me to the lanzón, a 14 ft. granite stela sitting in the heart of Chavín with sharp faces depicting an anthropomorphic figure, akin to a Chinese waving cat with a medusean head, with strands of snakes for hair. I stopped without meaning to, shocked by the beauty and energy of this figure greeting me sideways from a breach beneath the earth, lit up from below with an emerald tinted light. bowed to it, imagining what it would be like when it rains, as it does during the designated season in the North, when the water channeling system beneath the complex creates roaring sounds that supplemented the shamans’ and practitioners’ psychedelic experience, which they undertook in order to undergo spiritual transformation and spiral into a new, better understanding and manner of living.

Reflecting on 2025, I, as Marianne, was thinking about De Quincey’s palimpsest mind metaphor––the mind a parchment written on, then written over. The memory of this quote came from all the past I constantly immersed in this year, all the history of Peru’s peoples and landscapes I walked through. I felt drenched by the truth of Graham Hancock’s suggestion that humans are “truly a species with amnesia.” I was given the privilege to over and over find myself in the delightful state of philosophical origin: wonder. My mind spiraled in wonder about how little I was able to know about them, but how multidimensionally connected I felt to these peoples of the past, witnessing them pose the same questions and desires about life, transcendence, existence and employing such similar means of achieving some semblance of answers carved in stones and held in quiet, sandy graves.