Angelology

James Wetzel

The obscurity of scripture is actually useful; it births forth multiple views of the truth and ushers them into the light of knowledge, where one person interprets the text one way, another in another way.

--City of God, 11.19

Augustine knew what to believe about angels. The bad angels—the ones who separate self from God and fall into laborious, ill-fitting bodies and darkened perspectives—stay bad. Once a demon, always a demon. Nothing good ever comes out of hell. Meanwhile the good angels—the ones who are too busy trafficking in divine light to give much thought to self—enter into a sacred space of resolve, lodged somewhere deep within their inner recesses (if they ever would be inclined to explore). These angels have been evacuated of all motive to leave heaven and join the company of the fallen. They have become, like the dutiful elder brother in the prodigal’s tale, expert at staying home. For this they get to be angels proper. The improper angels, despite a veneer of wanderlust, are just angels stripped of their angel-constituting radiance: they are not-angels.

Augustine clearly felt drawn to an antithesis, fixed and final, between demon and angel. But such an antithesis, however central to what he takes his catholic faith to require him to believe, is not what preoccupies him in the thick of his angelology. His heart’s desire is to solve the mystery of angelic diversity. How do you begin with a chorus of angels, all perfectly attuned to one another and to the rest of the divinely orchestrated order of things, and end up with a permanently rent cosmos? What, in other words, is the story that gets you to antithesis?

Augustine’s angels are, in their original essence, the inseams of nature. They are ushered in with first light. God says (Genesis 1.3), “fiat lux”—“let there be light”—and there you have it: the angels come to be. The light that they essentially are is not material, however, not the stuff of moons and fiery orbs (a subsequent creation); through subtly articulate illumination, angels weave the web of love and intelligibility that transforms a collection of unrelated things, knocking into one another throughout an endless night, into a divine harmony. But being light such as that, their relationship to the night is a dicey proposition at best. Genesis 1.4-5: “God separated the light from the darkness and called the light day (diem) and the darkness night (noctem).” Augustine notices that nowhere in Genesis does the text ever say that night is a part of what is made (there is no facta est nox).

God creates the light that funds daytime—the stretch from morning (mane) to evening (vespere)—but night, the child of separation and darkness, is a different matter. Augustine leaves darkness to demonization and, from in between the lines of Genesis, digs out perhaps the greatest puzzle of his theology: that some angels, but not others, would choose to break from lives of reasonable light and invent darkness. His garden-grown Adam, when having to decide between an illuminated life with a skygod and something more down-to-earth, makes an analogous choice. The human story is not unrelated to the fault line in angelic nature.

On the first of April 2019, a day that fell for me into a time of introversion, when I was weighing endings and wondering whether I could, without pretense, venture spirituality with my philosophy students, I received by way of email a slim, self-published volume on the materiality of eternal life. It had the feel of a manifesto. Its language was urgent, open, insistent. The author, Jean Bitar, a retired Brazilian psychiatrist, had spent decades looking for the right words to convey to seekers and skeptics his experience of an overlap between the worlds of the living and the dead, of an afterlife, but in the here and now. It had been for a much younger Jean a full year of living ecstatically, as if his entire being had shifted to something radically off kilter, albeit in a good way. For most of us, mundane experience seems more tied to use than to beauty. I use my senses to negotiate the demands of my material existence; the beauty that interrupts my labors and redirects my attention to present things, apart from use, is occasional and usually unbidden. When the occasion comes too seldomly, I lapse into a low-grade depression or lose myself in ponderous questions about why things are as they are. (The disjunction is, of course, not exclusive.) For a year Jean had no use for ponderous questions. It was enough for him to live within a beauty that was mysteriously refusing to yield ground. But he was not drunk on a mystery or unaware that a preponderance of beauty in one’s experience is likely to seem to others as, well, just too weird. “In the beginning,” he writes, “I tried to talk about my ecstasy. My friends would—almost instantly—find a way to change the subject.”

The year of living ecstatically did come to an end for him, and when it did, Jean faced not only the dialectical impasse with his friends and family but also the one with himself. For if moving into an altered state of being is like having a brand-new sensation, a bit of sensational bliss, then it is only a matter of time before having to remember the sensation in its absence slips into doubts about ever having had the sensation at all. I think of this slide as the mysticism of diminishing returns. It is depressingly common.

But Jean, though he used the language of sensation, preferred to frame his experience, both in and out of ecstasy, in the idiom of vibration. If I follow him, the thought-picture is basically this: Imagine that your body, the one you can see simply by looking into a mirror, is only your visible body. You have higher registers of bodily existence at higher levels, or quanta, of vibration. What you may be inclined to think of as your death is actually a shift in your baseline perception of what your body is. You trade up, so to speak, and what was once too energetic for you to see is now what you see without effort or imagination. Your “old” body, no more now than a painted image, becomes correspondingly dream-like. Within the context of this framing, Jean’s year of living ecstatically had pitched him between worlds—two contrary pulls of the imagination—without allowing him to settle into either. No wonder he lacked the words to describe where he had been.

Jean sent me Immortality Is Material on the supposition that I would find its spiritually materialist vision of life akin to my own. All he knew of my writing at that time was an essay I had written, still in draft form but available online, on death and the afterlife. It never would have occurred to me, there or elsewhere, to invoke vibrational quanta to describe body’s endlessly metamorphotic love of soul (I am not that cool). But there was something about Jean’s openness to a transgressive imagination, more playful than anxiously self-aware, that resonated with me. (I tend to think that religious truths are mostly truths of the imagination, minus the fear.)

I wrote him back, while we were still in the mode of Prof. Wetzel and Dr. Bitar, men with CVs, and told him that I would read Immortality Is Material within about a month’s time, other obligations permitting. But I gave into the impulse to begin reading right after clicking the Send button. I got through a first read a couple of hours later and immediately wrote Jean back, brimming with gratitude and enthusiasm. Now we could be students together; neither of us was angling for authority.

And as it turned out, my impulse proved to be prescient. Jean had a heart condition, and we would have little more than two weeks to find a bridge between his antidogmatic, quasi-scientific speculations and my fondness for unloved religious truths—both ventures of the imagination. In the last email I would send to him, on the 17th of April, I asked him for more biographical detail. He knew he was dying, and I knew that I wanted to remember a person, not parse a theory. But he never wrote back. His death left a void where I would have liked to tell a story—or continue one.

The line that early in Immortality Is Material arrested my attention was this: “The prospect of turning into a spirit is appalling.” Provocative statement, given the rosy connotations of a spiritual transformation, but what did Jean mean by “turning into a spirit”? One thinks perhaps of the ancient pagan underworld, a murky place of bloodless shades and ghostly disappearing acts. Here loss masquerades as survival. Appalling. A similar masquerade is arguably at work in the life of a fully bodiless soul, freed from even the underworldly Elysium, where body-attire is always pleasantly light and able to be recycled. But my own imagination for agonized spiritualization tends toward the domain of my father’s piety.

Now we are back in the realm of the angels and what Augustine, and my father, would have us believe about them. My father died of complications of ALS and dementia in November of 2016. The essay of mine that Jean read and felt some kinship for, enough to reach out to me, was very much my attempt to come to terms with my father’s piety and to some degree to eulogize it. Not that anyone reading the essay would be able to tell. I have never been able to give much in the way of words to what bound my father and me to a common religious vision and then pulled us apart, into siloed pieties. Dad certainly believed in heaven and hell, in demons and angels proper, in the father in heaven and his son on earth, in antithesis. He was a true believer. No doubt he expected to see not only Jesus in the afterlife and all of the marquee saints, but also his parents, Nancy and Ferdinand, the German Shepherd he grew up with, and most importantly, his beloved wife, Martha, my mother, to whose happiness he devoted the better part of his adult life. I could never bring myself to believe in the afterlife in quite that way, even though I had no sophisticated alternative that wasn’t at root my attempt to shield myself from my own desire to see friends and family and the family dog in a big reunion in the sky.

I suppose I fancied myself the seeker between the two of us. But that wasn’t very fair to my father, to whom I was an enigma he sought, if not to fathom, at least to embrace. (When I went through his office materials after his death, I discovered that he had saved and annotated all the letters and papers I had sent him over the years. Mostly he underlined things and put a question mark next to obscurities. There were lots of question marks.) I was also overlooking the possibility that my father’s desire to negotiate the passage between life and afterlife with familiars was less a desire for closure than for company. I have to believe that the man who spent more than sixty years puzzling over the terms of my mother’s happiness, to ambiguous effect, had to have some idea of the limits of closure. Even in heaven. In any case, the angels above and the demons below are not endings to stories; they the question marks that God puts next to perplexing human passages.

Consider Augustine’s Lucifer. He is the paradigm angel on both sides of an ancient and yet ever-new divide. As the Light-bearer, the bringer of divine illumination, he comes to be not in time (in tempore) but along with it (cum tempore). Lucifer doesn’t have a birthday; no angel does. To suggest otherwise would be, for Augustine, to bungle the intimacy that angels have with time. Angels are of time’s essence; without them, there would be no eternal times (tempora aeterna), and time itself would run out of time and cease to exist. It is not at a particular time, then, that the Light-bearer becomes the Prince of Darkness. That transfiguration is written into every moment of existence. When Augustine tries to explain how this could be (for it does seem like a slur on creation), he suggests that Lucifer lacked prescience. He lacked the vision of his future self as firmly constituted within an unshakable divine embrace. The insecurity—fear of the future—drove Lucifer into darkness.

The suggestion is odd and yet telling. A being who comes to be with all of time is not likely to lack a sense of the future. If Lucifer does lack prescience, then he has become dissociated from his own self-knowledge. That too is the deliverance of every moment. It is also true that Lucifer will never know himself other than as the Light-bearer, as one of the good angels. When God, the only essentially eternal being, consigns Lucifer to life as the Prince of Darkness, we have the spectacle of the angel being forever denied self-knowledge. We can take this to be a picture of punishment. Lucifer sins for all of time—he is constitutionally faithless—and God forever shuts the door on this most prodigal of sons. While I hardly want to be in the business of redeeming demons, I confess that I am drawn to a different moral: that time is not a container. This is what the angels, high and low together, picture for us. There is no life in-between a time before time and a time after; there are only lifetimes. The angels cling invisibly to one another. Self-knowledge remains an open door. (Honestly, I can well imagine having this argument with my father in heaven. He would no doubt bring up Jesus. The Devil too.)

Jean reminds us that myths and symbols are objects of contemplation, not explanatory cudgels: “By contemplating them, our highest mental vibrations will come close to the filtered-out vibration that originates them and just that will facilitate transcendence.” The reminder is itself the offer of a grand mythology.

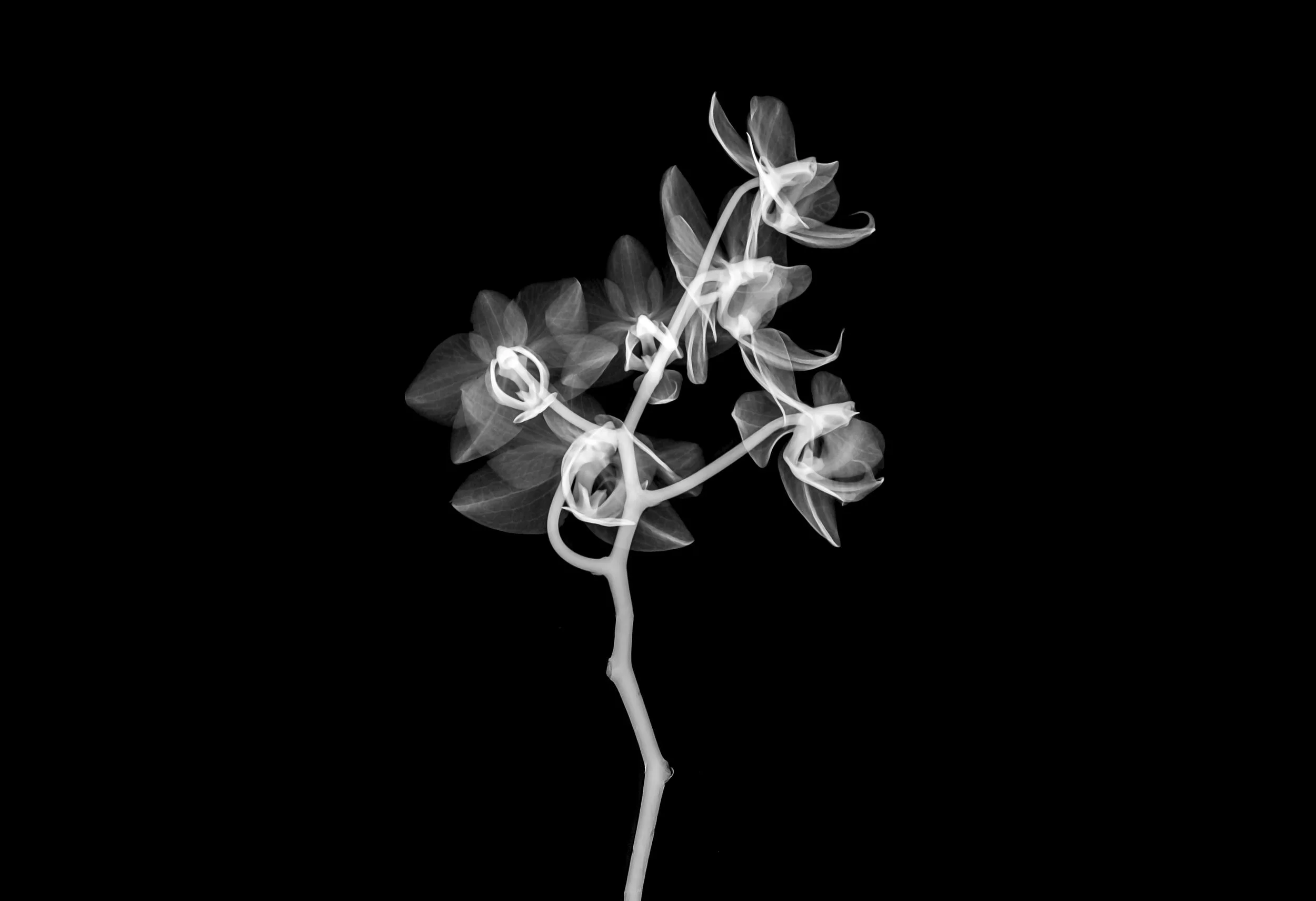

When I think of angels, I think of the stories that they make possible. Our lives, like our stories, hang like orchids in the midnight air.